Loss. Destruction. Small Miracles

Visiting Kfar Aza 8 months later

Traveling south, some 8 months after October 7th, I feel ready, I hope, to see some of the destruction wrought on that terrible day. The hard news of last week, 4 more hostages declared dead - Chaim Peri, 79, Amiram Cooper, 84, Yoram Metzger, 80, and Nadav Popplewell, 51 - the first 3 from Kibbutz Nir Oz, Popplewell from Kibbutz Nirim, and 35 year old Dolev Yehud’s body identified through DNA findings in Kibbutz Nir Oz. Yehud was buried last week, mourned by his wife and 4 children, one of them born after October 7th. Read more here

I know we also have the joy of Saturday’s miraculous rescue of 4 hostages. But all I could think about was the sadness of those families not reunited with their loved ones. Those families who fear that a hostage deal will crumble. Those families who wonder what will it take to bring their loved ones home, if ever.

Driving down Route 232, a mostly 2-lane road which ambles past pastoral farming villages and fallow fields, I anxiously look for signs of the death and destruction that marked October 7th but the road is quiet, newly paved in some parts, the burned and shot out cars, let alone the bodies that lined the road, long ago collected, identified and buried.

One of Yoram Metzger’s children said that regardless of how his father died, he doesn’t blame the IDF, if it’s discovered that is that the IDF’s entrance into Khan Younis played a role in their deaths. The responsibility, he said, rests solely on Hamas. Chaim Peri’s daughter, asked her father’s forgiveness, “we tried so hard but we failed to bring you home.” Tami Metzger, who’s aged about 1000 years since October 7th - captivity wasn’t kind to her let alone worrying about her husband - said goodbye to Yoram in a Gaza tunnel before leaving him for freedom in November. She struggled to express her pain let alone her anger at the government’s lack of ability or will to put together a hostage deal that might have brought her husband home alive.

Arriving at Kibbutz Kfar Aza, I wait for the rest of my group, enjoying the soft morning air, so much nicer than the very hot early summer heat in Jerusalem. I look out at the quiet fields, the trees waving in the breeze. It’s hard to believe the horror that happened here.

I’m waiting to meet up with kibbutz member, Gili, temporarily living on the coast at Kibbutz Shefayim. Gili is meeting up with Jane, who in her pre-retirement role at the San Diego Federation knew so many people in the southern communities of the Eshkol region well. Today, Jane is finally visiting, paying her respects and seeing for herself what October 7th meant to a small community like Kfar Aza, where Jane has friends who didn’t survive that day.

We drive up the road. Plants wave festively from the porch of one house while across the way, another home gapes open grotesquely, blackened by smoke, destroyed by RPG fire.

Parking, we walk over to Gili’s house as she points out where Ofer Libstein fell in defense of Kfar Aza early that morning. He was the head of the Sha’ar Hanegev Regional Council, and one of 7 out of 14 members of the kibbutz’s civil defense team killed that day. Gili reminds us that the due to a change in the rules, weapons were stored in a central area, and not in one’s home, making successful defense in the early hours of October 7th almost impossible.

We stand in Gili’s safe room, essentially a small bedroom, where she sheltered with her husband and her 4 year old grandson for 30 hours. Outside, she showed us where the first Hamas terrorists arrived on paragliders, landing 100 meters away from her home. Somehow, they didn’t come to her home or her neighbors, but bullet holes pockmark her walls where terrorists shot through her windows, one bullet firmly lodged into her refrigerator.

“I lived here for 22 years. I believed the border fence would keep us safe,” says Gili. In her safe room that day, she wondered, “Maybe G-d will save us. Maybe the universe.” (Read more about the failure of the fence, Israel’s Maginot Line here)

When the army finally arrived, Sunday morning, October 8th, a young soldier told her, “get some water and food, and go back into the room for a bit longer.” Breaking into sobs, she told him “no way,” and after covering her grandson’s face with a t-shirt, they were walked to a safe area. Her grandson later reported that he saw the bad things he wasn’t supposed to see, from the dead bodies that littered the road to the destroyed kibbutz homes.

As Gili walks us around, she shares stories, some of them ones I know. Lilli Itamari, murdered with her husband Ram, their home burned (it took 3 weeks to identify their bodies), endlessly asking for help on the kibbutz WhatsApp chat that morning. Nobody could help her, Gili reminds us, including another wounded kibbutz member who died right by her house. Her own adult son and a friend, went out initially to help realizing there was nothing they could do other than try and save themselves. Successfully getting back home, they listened to the cries of the 10-month old Berdichevsky twins next door. Their parents were killed early that morning. It was 12 hours before the army was able to rescue the babies who thankfully survived that day, and are being raised by their aunt and grandparents.

I thought about a conversation I had the other day with a visiting college student. We talked about resistance movements and violence, wondering why are they almost always connected. Why does a movement or an idea seem to always find its way, and often its success through violence? I went looking for answers but didn’t find what I was looking for really. I was reminded again of this quote of Gal Beckerman, from his book, The Quiet Before: The Unexpected Origins of Radical Ideas. I’ve probably quoted this before…because I like what it makes us consider in terms of violence within a stated cause.

“People don’t just cut off the king’s head,” he writes. “For years and even decades they gossip about him, imagine him naked and ridiculous, demote him from deity to fallible mortal (with a head, which can be cut).”

Enough years of radicalizing Gazans, of making those people on the other side of the fence - in Kfar Aza, in Be’eri, in Nir Oz, Sderot, Ofakim and more - become not just Israelis but mortal enemies. Not just Zionists but unworthy of remaining alive. Not just Jewish but belonging to a country so wrong that its people are just cannon fodder (no different than Gazans as well), and anything we do to them is okay in support of our cause. Radical thinking made others equally worthy of murdering and maiming, from Thai workers to Bedouins to people of Filipino, Nepali and Tanzania background, to name a few.

Cutting off their heads. Cutting apart their bodies. Destroying their homes, their families, their livelihoods, along with capturing them and bringing them home to endure endless captivity, in Gazan apartments - with journalists as it turns out - as well as tunnels, in their pajamas, without their glasses, “naked and ridiculous,” so to speak, is then perfectly fair. Right?

I recommend reading this not easy-to-read but thoughtfully stated essay, In Darkness All Is Black: Exploring the Realities of Violence by the Israeli State and Hamas. The researcher compares and contrasts Hamas and Israel with a focus on some of the violent history between them, especially in this last year. “The evolution and nature of Hamas illustrate the difficulties of applying the nomenclature of terrorism. Hamas is a political party, a social movement, an armed resistance group, and until recently a governing entity. It has participated in politics, governed, and provided social welfare. It has also coerced and harnessed the population of Gaza to serve its ends, and committed violence against Israeli combatants as well as non-combatant civilians, often indiscriminately.”

This paragraph also reminds us of the violent resistance that is a part of Israel’s early history. “The birth of many modern states went hand-in-hand with the use of extreme violence, which some of the fighting parties labeled as terrorism. Israel was no different. Consider the Zionist paramilitary Irgun blowing up the King David hotel in Jerusalem in 1946, the Lehi and Irgun groups committing the Deir Yassin massacre in 1948, or the Haganah forcibly displacing Palestinians. In their own eyes, they were fighting for independence. But to the British and Palestinians they were terrorists. In these situations, authorities often respond with indiscriminate violence that will likely be reciprocated in kind. Both French actions and the counteractions of Algerian insurgents during the French-Algerian war of 1954-1962 offer a case in point. The brutality of Hamas’ violence at close quarters and the careless application of industrial-scale firepower by the Israeli state fit squarely into such historical dynamics of violence between resistance and occupation.”

The researcher does not give enough credence to the brutal history of anti-Jewish violence in Israel, (let alone how the Turks and later the English pitted Arabs and Jews against each other, from the 1830’s with peak moments like the 1929 revolt and the late 1930’s. (Read more here). Not all of the article’s analysis feels right, including an assessment of Israel’s brutality in terms of aerial bombing during the current Gaza war, especially when the numbers have been reassessed because of Hamas Ministry’s inconsistent counts, suggesting that fewer women and children have been killed, perhaps because Israel hasn’t been targeting them. I’m not suggesting that civilians haven’t been killed, nor that the last 8 months have been easy for non-combatants. (Read more here)

Standing in Kfar Aza and later at the Nova Festival site (in some ways even more tragic at first glance than the kibbutz as it is essentially a plot of dry earth, now a memorial with flower markers and pictures for every one who was killed or kidnapped from the festival).

One can only imagine how amazing it was early that morning, as the sun rose and the music played, colorful decorations prettifying the space. Looking at the fields across the way and the skinny trees all around, I understand how easy it was to mow down the 362 people who really had nowhere to hide.

We walk back to our cars. One woman who’d joined us at Kfar Aza, she’s from Giv’im further South, shows me a video taken from their safe room on October 7th, fierce fighting right outside the entry of their village. I watch shaking my head, grateful that their community wasn’t invaded that day. Her daughter who was also with us, knew many of the young people murdered that day. The row of young people’s housing on the kibbutz was destroyed - by RPG fire and more - so many of them were killed or taken hostage.

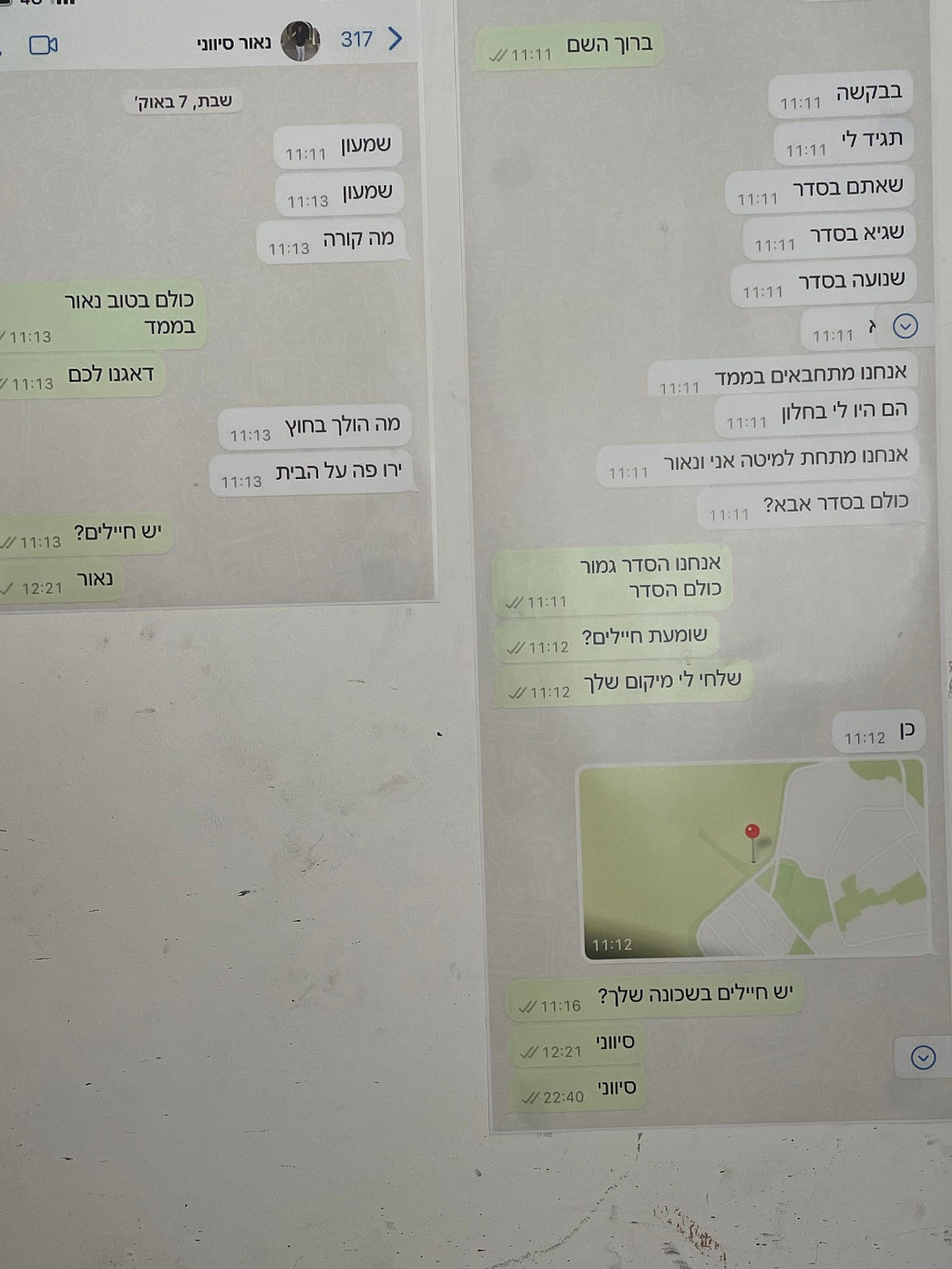

One of those little homes, really just 2 rooms, had been made into a little museum by the grieving family. Pictures of their final, frantic whatsapp chats with family hung on the wall, the last question asked, “are there soldiers?”

Silence marks that last unanswered text message.